“Am I Doing It Right?” (And Why That’s the Wrong Question)

Sarah in Warrior II.

Have you ever glanced at the person next to you in Warrior II and wondered, Am I doing this right?

Sometimes that question is about comparison.

But sometimes it’s about something deeper:

If I don’t get this exactly right, am I going to hurt myself?

That concern is understandable — and very human.

Modern anatomy shows every body is different

In traditions like Ashtanga — which evolved in the 20th century from a marriage of yoga and gymnastics — posture, discipline, and consistency are central.

Clear alignment cues can build strength, control, and safety, especially in repetitive transitions like chaturanga, where shoulder position and core engagement truly matter. Alignment can guide the intention of a posture.

Alignment has value.

And, modern anatomy has helped us understand something important: there is no single “correct” shape that fits every body.

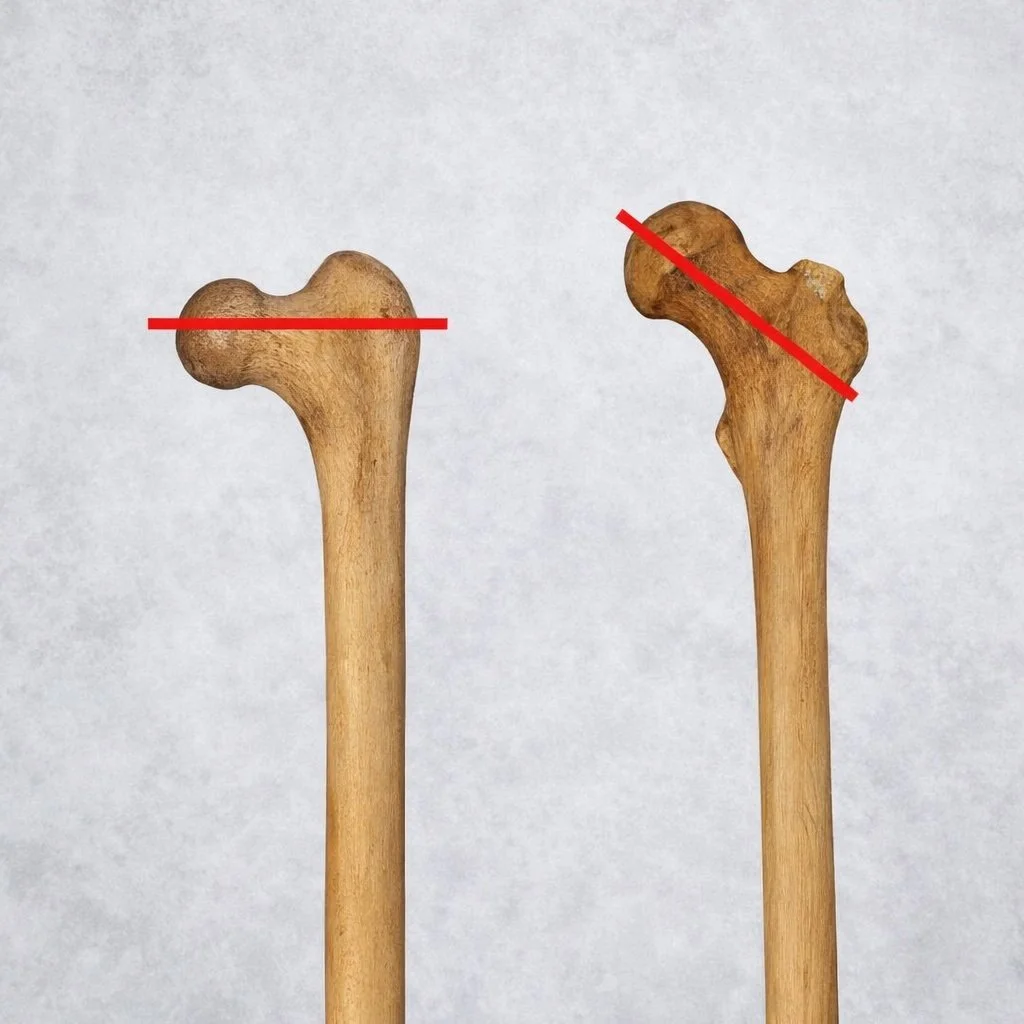

In his lecture series Anatomy for Yoga, Paul Grilley (the founder of Yin yoga) explains that skeletal structure varies dramatically between individuals. For example, hip sockets differ in depth and orientation. Femur lengths vary. The way your pelvis is built influences how your thigh bone rotates.

Two students can follow the same instruction and create completely different shapes. And both can be structurally sound.

Two left femurs. The inclination of the neck is 40° different. The ability to abduct would be 40° different. For more examples visit Yoga Studies with Paul and Suzee Grilley.

Function or aesthetics

Grilley inspired much of the work by Yin educator and author Bernie Clark. In his book Your Body, Your Yoga, Clark reminds us that yoga is functional, not aesthetic. The purpose of a posture is to create appropriate stress in tissues, not to achieve a universal image.

In her courses, workshops, and book Yoga Biomechanics: Stretching Redefined, biomechanics researcher and yoga educator Jules Mitchell bridges the gap between traditional yoga instruction and contemporary exercise science. One of her key points is that tissues — muscles, tendons, ligaments, and fascia — adapt to mechanical load over time. They respond to stress progressively, not instantly.

In other words, flexibility and resilience are not created by reaching a particular shape. They are built through repeated, manageable exposure to load — the gentle, steady stress your muscles and connective tissues experience when you hold or move through a pose.

Mitchell draws from strength and conditioning research to explain that the amount of force applied, how long it’s applied, how often it’s repeated, and how well the body recovers all influence how tissues respond. When load is appropriate and progressive, tissues remodel and become stronger. When load is excessive, repetitive without recovery, or applied with fatigue and poor control, injury risk increases.

This shifts the focus away from achieving a specific joint angle and toward managing intensity and repetition. A knee not reaching 90 degrees in Warrior II does not inherently make the pose unsafe. What matters more is whether the tissues involved are prepared for the load being asked of them — and whether the practitioner is moving with control rather than strain.

From this perspective, safety in yoga isn’t about chasing a visual standard. It’s about applying stress in a way the body can integrate and adapt to over time.

So what actually keeps you safe?

Not perfection, but awareness.

When breath becomes strained, when joints feel compressed or sharp, when you’re forcing range instead of exploring it — those are meaningful signals, like little red flags. When breath is steady, effort feels muscular rather than painful, and transitions are controlled, your body is supporting itself intelligently.

Think of alignment cues as invitations. They help you orient your structure. But they are not ultimatums.

Instead of asking, Does this look right?

Try asking:

Can I breathe here?

Do I feel stable?

Is this sensation sustainable?

What is the intention of this shape?

Those questions shift the focus from performance to presence.

Alyssa demonstrates the use of blocks in lizard lunge.

Props are your friends

Yoga was never meant to make every body look identical. It was meant to cultivate awareness inside your unique body.

And as that awareness grows, so does your ability to adjust.

Sometimes that adjustment is subtle — softening your jaw, bending your knee, slowing your breath. And sometimes it’s tangible — reaching for a block, using a strap, or choosing a variation that supports your structure.

Props aren’t a sign that you’re doing less. They’re a reflection of what you’re learning. A block under your hand doesn’t make the pose less powerful — it often makes it more sustainable. It helps distribute effort more evenly. It can reduce unnecessary strain and allow the tissues involved to do the work they’re meant to do.

That’s not “making it easier.” That’s practicing intelligently.

So next time that thought arises — Am I doing this right? — pause.

Breathe.

If you can breathe steadily, feel stable, and move with control, you’re not falling behind. You’re practicing with discernment. And that’s far more protective — and far more powerful — than chasing a perfect shape.

Jess demonstrates the use of props in a wide-legged forward fold.

Practice Suggestions

If you’ve ever worried about “doing it wrong,” here are a few simple ways to practice with more intelligence and less fear:

1. Use the Breath Check

In any posture, ask yourself:

Can I breathe smoothly through my nose?

Is my exhale steady?

Does my jaw feel soft?

If your breath becomes sharp, held, or strained, that’s information. Back off slightly. Often one inch of adjustment makes the pose more sustainable and effective.

2. Distinguish Effort from Pain

Muscular effort might feel:

Warm

Shaky

Fatiguing

Joint pain often feels:

Sharp

Pinchy

Compressive

Localized deep inside a joint

If something feels sharp or unstable, come out or modify. That’s not weakness; that’s discernment.

3. Treat Alignment Cues as Experiments

When you hear an alignment instruction, try it on — but don’t assume it’s mandatory.

Ask:

Does this cue improve stability?

Does it make my breath easier or harder?

Does it feel supportive in my body?

Alignment is guidance, not a pass/fail test.

4. Slow Down Repetitive Transitions

In movements like chaturanga, step-back transitions, or repeated vinyasas, go slower than you think you need to.

Control builds strength.

Speed often hides compensation.

You can always drop your knees.

You can always skip a vinyasa.

That choice often protects your shoulders more than pushing through fatigue.

5. Make Friends with Props

Try this experiment:

Take a block even when you could reach the floor.

Notice what changes:

Is your spine longer?

Is your breath steadier?

Do your hips feel more balanced?

Props don’t necessarily make the pose easier; they can make the load more appropriate.

6. Replace “Am I Doing It Right?” With:

Can I breathe here?

Do I feel stable?

Is this sensation sustainable for five more breaths?

If the answer is yes, you are practicing skillfully.

7. Ask Questions

If you’re unsure, ask your instructor after class:

“What should I be feeling in this pose?”

“How can I make chaturanga safer for my shoulders?”

“Is this sensation normal?”

Curiosity builds confidence.

Sources & Further Reading

Clark, Bernie. Your Body, Your Yoga. 2018.

Mitchell, Jules. Yoga Biomechanics: Stretching Redefined. 2019.

Grilley, Paul. Yoga Anatomy and Anatomy for Yoga.

Neumann, D.A. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System. 2017.